A Terminal User Interface (TUI) is a user interface based on a terminal. Yes, that's it.

And what's so special about them? Don't we already have GUIs that better suit current visual needs?

Yes, it's true that GUIs can be better for certain cases, but if you're a software developer like me, you know that most of the time we spend it in the terminal.

Naturally we feel the terminal as a home, a place where we can do whatever we want and that represents the starting point for all the projects we undertake.

That's why I decided to embark on the task of creating a TUI and thereby learn how they work, and maybe in the future carry out a creation with a higher degree of complexity.

What to build?

This was the first question I had to ask myself. While exploring, I found the GitHub repository Build Your Own X, a list of guides you can follow to learn to build your own "whatever". They have everything from CLIs to building kernels and operating systems (a topic I'll surely explore and share on this blog).

This repository represented a starting point for me. I explored the options and came across the article Visualize your local Git contributions with Go.

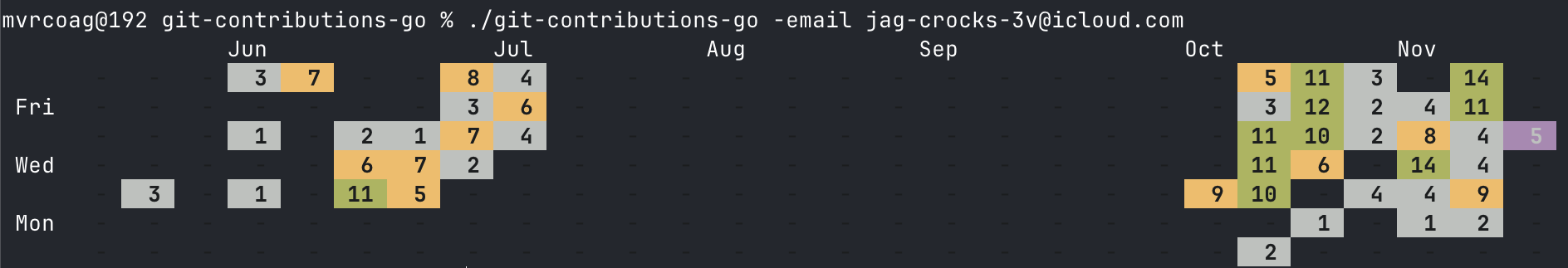

I was decided: I was going to build a TUI that would show me my local Git contributions.

Key learnings

I could write my entire building process, but the reality is that the original article exists and I consider it a better reference for anyone who wants to build this tool themselves.

Instead, I'm going to share some key learnings I gained throughout this gratifying experience.

1. Flag

Go is wonderful for building TUIs. It has a package called flag. flag handles,

among other things, parsing the elements passed to the command as flags.

Let's take an example, consider the command git commit -m "...". In this example the flag would be -m, and this flag has an associated value

"...". Go's flag package abstracts all this from us and with a few lines of code we can parse values:

package main

import "flag"

func main() {

var folder string

var email string

flag.StringVar(&folder, "add", "", "add a new folder to scan for Git repositories")

flag.StringVar(&email, "email", "your@email.com", "the email to scan")

flag.Parse()

if folder != "" {

scan(folder)

return

}

stats(email)

}2. Directories and recursion

One of the needs of the tool I was building was that it should be able to, given a root directory, recursively search all subdirectories for the existence of Git repositories.

Although I had worked with recursion before, I had never done it focused on a file system.

Again, Go makes interacting with the operating system's file system very easy and the code becomes very easy to understand.

func scanGitFolders(folders []string, folder string) []string {

folder = strings.TrimSuffix(folder, "/")

f, err := os.Open(folder)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

files, err := f.Readdir(-1)

f.Close()

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

var path string

for _, file := range files {

if file.IsDir() {

path = folder + "/" + file.Name()

if file.Name() == ".git" {

path = strings.TrimSuffix(path, "/.git")

fmt.Println(path)

folders = append(folders, path)

continue

}

if file.Name() == "vendor" || file.Name() == "node_modules" {

continue

}

folders = scanGitFolders(folders, path)

}

}

return folders

}Pretty simple. The key here is that when it's identified that we're in a directory, that it's not a git directory and that it's also not a "vendor" or "node_modules" directory, then recursion is used to iterate now at a deeper level, looking for new subdirectories.

Quite interesting how Go makes this so easy.

3. os/user

When we build CLIs or TUIs it's quite common for all the information to stay local, however many times it's still necessary to store the data somewhere.

When we develop for web it's very common for this data storage place to be the database. But if we think about CLIs or TUIs (and even sometimes it also applies to web) a database becomes overkill. It's too much for the type of information that will be saved.

A common approach is to use a local flat file where information can be stored and the state of the tool we develop can be preserved. This is especially common for configurations, however it can be used for any type of information as long as we maintain a clear structure.

A common place to store this type of configuration files is the user home. This home varies according to the operating system, and the relative path will also vary depending on where our tool is being executed from.

This adds a certain level of complexity due to the variable nature of the situation, but thanks to the os/user package Go handles it very simply.

func getDotFilePath() string {

usr, err := user.Current()

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

dotFile := usr.HomeDir + "/.gogitlocalstats"

return dotFile

}Quite simple. This package already has a Current function that returns key information about the user executing the tool, information that already contains the HomeDir data, which we use to establish

the location of our .gogitlocalstats configuration file.

Conclusion

Go is excellent not only for servers, but also for systems and tools that directly use the operating system as CLIs usually do.

I'm interested in developing my own operating system component, and without a doubt today Go has risen considerably in the ranking of what language to use for such task.

See you.